BY THOM HULEN | AUGUST 24, 2011

Cave Creek: Refuge for Desert Fish

Their presence testifies to the incredible nature of the Sonoran Desert

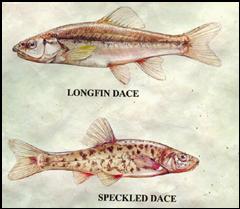

When most people think of Arizona or the Sonoran Desert they do not think about fish. Or if they do they think about the many species of game fish such as large mouth bass and rainbow trout that can be found in the several reservoirs that store water for agricultural and municipal uses. When informed that Arizona was home to at least 35 species (34 species are extant) of native fish, most of which lived in desert streams such as the Agua Fria, Colorado, Gila, Salt, San Pedro, Santa Cruz and Verde Rivers and their many tributaries, people are usually imp ressed and often want to know more about them.

ressed and often want to know more about them.

Cave Creek, the tributary of the Salt River that provides the name for a community in Maricopa County, currently has at least four species of native fish that are adapted to the conditions common to desert rivers and streams.

To survive in a desert stream like Cave Creek fish have to be able to endure periods of low water levels and times when flood conditions prevail. When water levels are low water is often restricted to isolated pools and springs. Under these circumstances conditions can be extreme. Predation pressure can be higher because of relative scarcity of aquatic habitat, packing prey and predator closer together and increasing concentrations of animal waste products, adversely affecting water chemistry. Bass and sunfish are voracious and effective predators.

Floods can displace fish downstream and significantly alter the streambed, modifying microhabitat. Fish native to desert streams are adapted to this environment and can cope and even thrive.

In the latter half of the 19th century Americans decided to make Arizona and other western states a little more like home in the East. They introduced to many western rivers and streams a number of fish native to Europe and the Mississippi River drainage. Believing they were improving the fishery they unknowingly contributed to the decline of native fish. Rivers and streams were diverted and impounded for agriculture and hydropower, the range was overgrazed and watersheds were altered. These combined changes put a real strain on native fish.

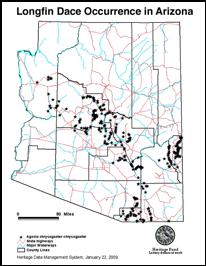

Presently Cave Creek has two species of native fish as well as six exotic species. Longfin dace (Agosia chrysogaster) and speckled dace (Rhinichthys osculus) are still common throughout their original ranges except that populations of these fish are more disjunctive and isolated than before. These fish feed on detritus, aquatic invertebrates and algae. Long fin dace can survive relatively high temperatures and low-quantity and low-quality water. They have been found in moist algal mats where there was not enough water to swim. Ammonia concentrations from their body wastes were at levels toxic to most species.

fin dace can survive relatively high temperatures and low-quantity and low-quality water. They have been found in moist algal mats where there was not enough water to swim. Ammonia concentrations from their body wastes were at levels toxic to most species.

Gila chub were present in Cave Creek until 1978. They were first recorded in 1950 in Cave Creek in the vicinity of the Desert Foothills Land Trust’s Jewel of the Creek Preserve and Spur Cross Ranch Conservation area. This fish was last observed in Cave Creek in 1978 near Seven Springs.

Why does it matter that native fish live in Cave Creek or any body of water? What good are they anyway?

Fish as well as any organism have a niche or function in an ecosystem that fits like a piece of a puzzle. Each species performs a role that complements other species in that system. Removing a species leaves a hole that impacts other species. In most cases the ecosystem is resilient enough to cope, or we perceive that the system is coping with one or more missing pieces, but there comes a time when the system can no longer support itself and it crashes. Ecosystem crashes are fairly common. One excellent example of this is taken from Yellowstone National Park. During the early part of the last century wolves were extirpated from the park; no one realized that the Lamar River would become degraded during the next 69 years as a result of this effort. What happened is this: the elk population in the Yellowstone area increased significantly because of less predation; the greater number of elk ate more plant material, so much so that most, in some cases all, of the streamside vegetation such as willow and nearby aspen trees failed to regenerate. With the loss of the streamside vegetation the stream banks became unstable and eroded, causing the silt load in the stream to increase, the streambed to straighten and in many cases lead to an incised (deeper) streambed.

When wolves were reintroduced in 1995 a more natural predator-prey relationship was re-established between wolves and elk. The numbers of elk decreased, thereby reducing feeding pressure on the vegetation. After a few years the willow and aspen started regenerating and the streambed now is approaching a healthier state. Who would have thought that wolves played a role in stream ecology?

The role native desert fish play in the ecology of the Cave Creek watershed is uncertain. They are part of the food chain and their presence certainly does add a bit of interest to the flora and fauna of the region. Their mere survival in an area famous for hot dry conditions testifies to the incredible nature of the Sonoran Desert. For this reason alone these desert fish should be allowed to thrive in our desert streams.

For more information on Arizona’s native fish, see the Arizona Game and Fish Department’s booklet, Arizona’s Native Fish Heritage. Copies can be acquired at no cost by calling or writing the Arizona Game and Fish Department, 5000 West Carefree Highway, Phoenix, AZ 85086, 602.942.3000.

Classic will host its 9th golf tournament on Saturday, September 16, 2010 at the Dove Valley Ranch Golf Club.

Classic will host its 9th golf tournament on Saturday, September 16, 2010 at the Dove Valley Ranch Golf Club.