BY MICHELLE KNOWLES, CERTIFIED PET AESTHETICIAN, SPA DIRECTOR |JULY 6, 2011

Summer shave-downs. Do they really benefit your pet?

Hair is the skin’s first physical barrier against toxins and pollutants in the environment.

Since skin is the largest organ on a pet, protecting it is vital to your pet’s overall health.

Since skin is the largest organ on a pet, protecting it is vital to your pet’s overall health.

A dog or cat’s hair follicles are arranged in groups consisting of primary hairs surrounded by secondary hairs. The density of hair depends on the breed and age of the animal. The softer the hair, the denser it is. The movement of the hair is controlled by the Arrector Pili muscle. Hair color and length are genetically predetermined. Hair does not last forever nor does it fall out at the same time. Shedding in intervals is nature’s way of allowing the skin to be protected during hair loss. Have you ever noticed those tufts of hair on the rear-end of your pet during shedding season? This is because shedding starts at the rear of the animal and moves towards the front.

Shaving strips the skin and hair of natural oils, clogs pores and exposes the skin to bacteria, pollutants and harmful UV rays. These factors intensify itching, allergies and irritation. While most people view shaving as a way to counter the symptoms of allergies, it actually can lead to a more in-depth problem and never is the solution. Length of hair will not reduce allergies for you or your pet. Regular and proper cleansing of the skin will. Usually, when a human is allergic to a pet it is an allergy to the dander of the pet rather than the hair. Dander is material shed from the body of various animals, similar to dandruff. It may contain scales of dried skin and hair, or feathers.

Avoiding shaving and using a properly pH balanced shampoo specific to your dog will go a long way in decreasing skin itchiness and irritation. (Pets have a pH of 6.5 - 7 while humans are 5.5) Dish soaps, hand soaps, baby shampoos or human shampoos will only intensify the symptoms. But that’s not all, while shampoo cleanses the skin, it also removes natural oils that must be replaced by a balsam/conditioner. Using a balsam in dogs isn’t to get out tangles but rather to replace the oils and give the skin a layer of protection.

The key to keeping your pet cool and having healthy skin isn’t by uncovering it with shaving, but rather by protecting it. Hair is a sun and wind barrier. The hair will raise and lower to insulate or ventilate the animal when cold or over-heated.

If shedding is making your house a mess, consider getting a de-shed treatment rather than a shave-down. Your pet will still have the necessary hair for controlling their body temperature and coverage to protect against bacteria and pollutants as well as harmful UV rays.

If you would like more information about de-shed, dog hair cycles and the proper shampoos and balsams, please visit us at ahsvet.com “The Tender Paw Day Spa” button.

A professional pet stylist with over 20 years in the field, Michelle has extensive experience with fear and trauma recovery, elderly pet care, and specializes in managing allergic and dermatological disorders. She is certified by the National Dog Groomers Association of America and Iv San Bernard School in Italy. She has also been published in national grooming periodicals such as “Groomer-To-Groomer.”

JULY 6, 2011

Genetic analysis splits Desert Tortoise into two species

RIVERSIDE, Calif. – A new study shows that the desert tortoise, thought to be one species for the past 150 years, now includes two separate and distinct species, based on DNA evidence and biological and geographical distinctions.

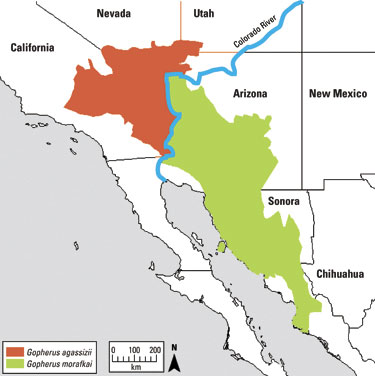

This genetic evidence confirms previous suspicions, based on life history analysis, that tortoises west and east of the Colorado River are two separate species.

The newly recognized species has been named Morafka’s desert tortoise (Gopherus morafkai) and represents populations naturally found east and south of the Colorado River, from Arizona extending into Mexico.

The newly recognized species has been named Morafka’s desert tortoise (Gopherus morafkai) and represents populations naturally found east and south of the Colorado River, from Arizona extending into Mexico.

The originally recognized species, the Agassiz’s desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) is listed as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act. It represents populations naturally found west and north of the Colorado River in Utah, Nevada, northern Arizona and California.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), which manages the recovery of threatened and endangered species, had already been treating tortoises on each side of the Colorado River as distinct populations The genetic evidence simply backs up previous observations, such as differences in life history and reproductive strategies.

"The two species have different habitat preferences," says Kristin Berry, a USGS biologist who has studied desert tortoise biology for more than 40 years and a coauthor on the study. "Morafka's tortoise prefers to hide and burrow under rock crevices on steep, rocky hillsides, while the Agassiz’s tortoise prefers to dig burrows in valleys."

Roy Averill-Murray, the desert tortoise recovery coordinator for the Fish and Wildlife Service said, "We appreciate the efforts of USGS and other researchers to increase our scientific knowledge about the taxonomy of the desert tortoise. The study's finding that the Morafka's desert tortoise is a new species confirms the Service's decision to evaluate this population independently from the Agassiz's desert tortoise, and will not change the status of either species under the Endangered Species Act or change existing recovery plans."

Distinguishing the two species required some historical detective work by the researchers. Desert tortoises were first described in 1861 by an Army physician, J.G. Cooper. But two of the original specimens were lost, possibly as a result of the San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906. Fortunately, Cooper had sent a third specimen to the Smithsonian — and its DNA helped researchers in their analysis 150 years later.

The study is published in the journal ZooKeys and authored by Robert Murphy of the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada, Kristin Berry of the USGS, and colleagues from University of Arizona, California Academy of Sciences and Lincoln University (Mo.).

Field research and travel for this study was supported by contracts from University of California Los Angeles, California State University Dominguez Hills, US Army Fort Irwin, USAF Edwards Air Force Base, USMC Air Ground Combat Center Twentynine Palms, California Department of Fish and Game, the Bureau of Land Management and the USGS.

Read a detailed FAQ about the study on the USGS Western Ecological Center webpage.

More information on desert tortoise research by USGS biologist Kristin Berry: www.werc.usgs.gov/boxsprings